Suntory Hall just released more photos from the latest "Chamber Music Concert for Wheelchair Users"(on Sep.21st at Blue Rose), which I produced the program and participated in. 4 years ago 51 students and guardians came and the number kept increasing steadily each year ever since. This year we exceeded last year's figure of 144. The photos speak better than words of the social significance of this concert series. It has been both privilege and honor to work on this project sponsored jointly by Suntory Hall and Nippon Music Foundation.

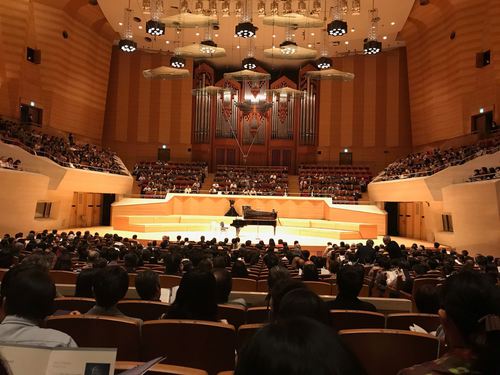

Today I listened to a famous baritone Matthias Goerne who sang Schubert's "Winterreise" at Suntory Hall. I liked his interpretation from the beginning but especially enjoyed from no. 15 song "Crow" to the end of the cycle. The last two songs were played without break and the last song "Organ Grinder" were played and sang with beautifully soft vioce and delicate nuances. When pianist Markus Hinterhauser hit his last notes, I wish I could have had about at least 10 seconds of silence to savor the feeling of hopelessness which Mr. Goerne and his pianist did so eloquently presented to us.

Yesterday, after taking part as a jury member for the Student Music Concours of Japan at Suntory Blue Rose, I walked to Suntory Concert Hall to listen to a recital given by 93 year old Pressler, who is a legend in chamber music and piano playing. To appear onto the stage and to settle into the playing seat, he needed a cane and an assistant's hand. But the anxiety of the audience disappeared quickly as soon as he hit his first note: everyone was entranced and started to listen with utmost concentration. I could almost hear the sound of breathing of people around me. How can an elderly man create such a magically rich world with his hands and feet? As the program progressed I heard some sniffles and during the encores, I saw many listened with teary eyes.

I am overwhelmed and shaken by the extent of the damages and sufferings caused by the giant earthquake and subsequent tsunamis on March 11, only to be followed by radioactive threats from nuclear reactors on the coast of Tohoku or Northeast Region of Japan.

Every year I spend two and a half months teaching at a university in Akita, one of the major cities of Tohoku or Northeast Region. Unlike adjacent prefectures (districts) Akita faces the Japan Sea, not the Pacific Ocean. And when the tsunamis arrived they were not so damaging.

The devastated areas are close to my heart because I know many of them. For the past several years, I have performed regularly in this region. And when the weather was mild, I frequently hiked the mountain trails of hard hit prefectures of Iwate, Aomori and Miyagi.

Just several days before the great earthquake struck, I had taken part in a chamber music concert in Akita City with two other musicians. One was Takeshi Sato, a young pianist who resides in Germany and another, Shinsuke Hagawa, a cellist who is active in Japan. Both hail from Akita. The packed audience and the three of us had enjoyed the exciting afternoon.

The program note included an interview with me which was held a week earlier. Below I include some excerpts:

Q: What do you remember about this Akita Atorion Music Hall?

A: Ever since the Akita International University (国際教養大学) opened its doors in 2004, I played many times here. To mention some events: three times with the Akita Atorion Chamber Orchestra; two lecture-concerts, sponsored by the university ; a Christmas concert, sponsored by this Hall; a duo concert in 2010 with Nuyoya, a marimba player, who resides in Germany. Through these events I met many music lovers and performers in Akita and neighboring prefectures and developed lasting personal ties.

Q: Who influenced you in your steps to become a professional musician?

A: Different people helped me in various phases of my career development. When I began to play at 3 years old, my teachers taught me the fundamentals of technique and musical sense. I think the basic skills which I acquired while very young carried me through in later stages. At Julliard School of Music, my teacher Joseph Fuchs, guided me as a father does toward his daughter. He illustrated to me with his unwavering stance toward music (even at the age of 90) what it takes to come closer to the true nature of music. He also taught me that through such continuous endeavors, moments of joy visit us unexpectedly.

Giuseppe Sinopoli, who suddenly passed away while directing an opera in Berlin in 2001, invited me to numerous big stages in Europe. I also had an opportunity to record violin and chamber concertos by Berg with him. Through several concert tours with him in Europe and Japan, I learned that a bona fide, first class musician always possesses his/her concrete vision of how to express a particular piece. And he/she has the will of steel, which never compromises, until he arrives at the actualization of his vision.

In New York, from time to time, the late Isaac Stern would listen to my playing in front of him. He taught me the need to retain a rigorous and strict stance toward music. I never forget the conversation with him right after his performance of Mozart concert. His view toward his own performance was shockingly objective and analytical.

Q: What should we look for in the coming chamber music concert?

A: When people hear the term "chamber music", some think of it as somewhat plain. But it is the most important genre in music. For composers, unlike an orchestral piece where many instruments appear, chamber music treasures most intimate interactions among a limited number of instruments.

Chamber music displays the most fundamental aspect of music -- the structure. Thus, it is a very important element in music. Recently, the music director of Suntory Hall (in Tokyo) and a world class cellist, T. Tsutsumi wrote in a newspaper, "Chamber music is the most basic part of music. I find that wherever chamber music is very popular, the level of music of that city is equally high and vice versa. I hope that Japanese musicians will have more opportunities in play chamber music and that Japanese music lovers begin to appreciate its charm more."

I cannot agree more with the sentiment of Mr. Tsutsumi, based on my past professional experience. I hope many people would come to chamber music concerts more often.

Q: Any message for young, aspiring musicians?

A: Music is like a dialogue. A musician shouldn't concentrate on her part alone, but must make effort to understand how the melody fits in the overall structure and flow of harmony. Don't miss any opportunity to play chamber music, and take serious interest in understanding the structure of music.

Every year I spend two and a half months teaching at a university in Akita, one of the major cities of Tohoku or Northeast Region. Unlike adjacent prefectures (districts) Akita faces the Japan Sea, not the Pacific Ocean. And when the tsunamis arrived they were not so damaging.

The devastated areas are close to my heart because I know many of them. For the past several years, I have performed regularly in this region. And when the weather was mild, I frequently hiked the mountain trails of hard hit prefectures of Iwate, Aomori and Miyagi.

Just several days before the great earthquake struck, I had taken part in a chamber music concert in Akita City with two other musicians. One was Takeshi Sato, a young pianist who resides in Germany and another, Shinsuke Hagawa, a cellist who is active in Japan. Both hail from Akita. The packed audience and the three of us had enjoyed the exciting afternoon.

The program note included an interview with me which was held a week earlier. Below I include some excerpts:

Q: What do you remember about this Akita Atorion Music Hall?

A: Ever since the Akita International University (国際教養大学) opened its doors in 2004, I played many times here. To mention some events: three times with the Akita Atorion Chamber Orchestra; two lecture-concerts, sponsored by the university ; a Christmas concert, sponsored by this Hall; a duo concert in 2010 with Nuyoya, a marimba player, who resides in Germany. Through these events I met many music lovers and performers in Akita and neighboring prefectures and developed lasting personal ties.

Q: Who influenced you in your steps to become a professional musician?

A: Different people helped me in various phases of my career development. When I began to play at 3 years old, my teachers taught me the fundamentals of technique and musical sense. I think the basic skills which I acquired while very young carried me through in later stages. At Julliard School of Music, my teacher Joseph Fuchs, guided me as a father does toward his daughter. He illustrated to me with his unwavering stance toward music (even at the age of 90) what it takes to come closer to the true nature of music. He also taught me that through such continuous endeavors, moments of joy visit us unexpectedly.

Giuseppe Sinopoli, who suddenly passed away while directing an opera in Berlin in 2001, invited me to numerous big stages in Europe. I also had an opportunity to record violin and chamber concertos by Berg with him. Through several concert tours with him in Europe and Japan, I learned that a bona fide, first class musician always possesses his/her concrete vision of how to express a particular piece. And he/she has the will of steel, which never compromises, until he arrives at the actualization of his vision.

In New York, from time to time, the late Isaac Stern would listen to my playing in front of him. He taught me the need to retain a rigorous and strict stance toward music. I never forget the conversation with him right after his performance of Mozart concert. His view toward his own performance was shockingly objective and analytical.

Q: What should we look for in the coming chamber music concert?

A: When people hear the term "chamber music", some think of it as somewhat plain. But it is the most important genre in music. For composers, unlike an orchestral piece where many instruments appear, chamber music treasures most intimate interactions among a limited number of instruments.

Chamber music displays the most fundamental aspect of music -- the structure. Thus, it is a very important element in music. Recently, the music director of Suntory Hall (in Tokyo) and a world class cellist, T. Tsutsumi wrote in a newspaper, "Chamber music is the most basic part of music. I find that wherever chamber music is very popular, the level of music of that city is equally high and vice versa. I hope that Japanese musicians will have more opportunities in play chamber music and that Japanese music lovers begin to appreciate its charm more."

I cannot agree more with the sentiment of Mr. Tsutsumi, based on my past professional experience. I hope many people would come to chamber music concerts more often.

Q: Any message for young, aspiring musicians?

A: Music is like a dialogue. A musician shouldn't concentrate on her part alone, but must make effort to understand how the melody fits in the overall structure and flow of harmony. Don't miss any opportunity to play chamber music, and take serious interest in understanding the structure of music.

From the concert in Sendai City, I traveled south to Yokohama's Minato-mirai Concert Hall to serve as a judge at the final round of All Japan Student Music Competition on November 29 and 30. This was the 63rd annual competition. A good placement here would open doors for any aspiring professional musician.

At this competition, it is difficult to grade participants quantitatively. What makes the task formidable is that in the final round, the contestants choose their own music. It would be easier to grade them if everyone played the same piece. How does one compare one student's playing the first movement of Sibelius' Violin Concerto and another Wieniawski's Faust Fantasy? The required technique for playing each piece is different. In general, however, the most important goal of any performer on stage is to convey something to each listener's spirit, and I graded the performers accordingly.

I remember clearly the winners of the elementary school and high school divisions. With excellent execution and mature interpretation the young girl played Saint-Saens' Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso. With calm and exquisite shades of sound, the high school boy played Saint-Saens' Habanera.

When the first day's competition was finished, a number of judges hopped on an elevator in the hall, and I spotted a young boy who had placed second in the elementary school division walking in with his mother. Though only a fourth grader and small in statue, he had played the third movement of Tchaikovsky's violin concerto with joie de vivre. I couldn't help sense his love for playing Tchaikovsky's pieces. Once in the elevator, he shouted, "I only placed second. I am not going to play violin anymore." I replied, "Are you going to give up for such a reason? There are many things that don't go your way in life. If all dreams keep coming true for many years, what will you do when you hit a wall then? Don't be so impatient; without patience your playing days are numbered." The small elevator became a psychiatrist's booth!

It is important to feel vexed and frustrated. I am sure this child who has experienced disappointments will make good progress in the future. As a child player I also had serious setbacks but got over them. Looking back at similar moments in my career, those were the precious events which drove me to mature and develop.

When an artist searches in earnest for the essence of his art, he may attain a special state of mind and bask in fulfillment, joy, and thankfulness for just participating in this art. I recall the words of a Japanese genius sculptor, R. Hajiwara, who had studied with A. Rodin in France but died young at thirty: "If I die young without accomplishing all I wanted to do, I shall accept such a fate which heaven gives me." I suspect these words were spoken in the final years of his brief life, but I empathize deeply with his serious and genuine stance. My goal for the next several years is to arrive at a similar mental state as he.

Lastly, there is something I wish aspiring child musicians in Japan will remember: that is, they should play as much chamber music as possible. Many European and American musicians enjoy playing chamber music from early childhood. This experience gives them a broad and full understanding of music, a different understanding of how solo parts fit in with an ensemble. Playing chamber music will also help a musician develop a better and multidimensional sense of sound and forms of expression. Young Japanese soloists put too much emphasis on playing and practicing solo pieces. I recommend they play more chamber music pieces and broaden their understanding of music.

At this competition, it is difficult to grade participants quantitatively. What makes the task formidable is that in the final round, the contestants choose their own music. It would be easier to grade them if everyone played the same piece. How does one compare one student's playing the first movement of Sibelius' Violin Concerto and another Wieniawski's Faust Fantasy? The required technique for playing each piece is different. In general, however, the most important goal of any performer on stage is to convey something to each listener's spirit, and I graded the performers accordingly.

I remember clearly the winners of the elementary school and high school divisions. With excellent execution and mature interpretation the young girl played Saint-Saens' Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso. With calm and exquisite shades of sound, the high school boy played Saint-Saens' Habanera.

When the first day's competition was finished, a number of judges hopped on an elevator in the hall, and I spotted a young boy who had placed second in the elementary school division walking in with his mother. Though only a fourth grader and small in statue, he had played the third movement of Tchaikovsky's violin concerto with joie de vivre. I couldn't help sense his love for playing Tchaikovsky's pieces. Once in the elevator, he shouted, "I only placed second. I am not going to play violin anymore." I replied, "Are you going to give up for such a reason? There are many things that don't go your way in life. If all dreams keep coming true for many years, what will you do when you hit a wall then? Don't be so impatient; without patience your playing days are numbered." The small elevator became a psychiatrist's booth!

It is important to feel vexed and frustrated. I am sure this child who has experienced disappointments will make good progress in the future. As a child player I also had serious setbacks but got over them. Looking back at similar moments in my career, those were the precious events which drove me to mature and develop.

When an artist searches in earnest for the essence of his art, he may attain a special state of mind and bask in fulfillment, joy, and thankfulness for just participating in this art. I recall the words of a Japanese genius sculptor, R. Hajiwara, who had studied with A. Rodin in France but died young at thirty: "If I die young without accomplishing all I wanted to do, I shall accept such a fate which heaven gives me." I suspect these words were spoken in the final years of his brief life, but I empathize deeply with his serious and genuine stance. My goal for the next several years is to arrive at a similar mental state as he.

Lastly, there is something I wish aspiring child musicians in Japan will remember: that is, they should play as much chamber music as possible. Many European and American musicians enjoy playing chamber music from early childhood. This experience gives them a broad and full understanding of music, a different understanding of how solo parts fit in with an ensemble. Playing chamber music will also help a musician develop a better and multidimensional sense of sound and forms of expression. Young Japanese soloists put too much emphasis on playing and practicing solo pieces. I recommend they play more chamber music pieces and broaden their understanding of music.

Yesterday I played the world premiere of Mr. Tokuhide Niimi's Second Violin Concerto with the Sendai Philharmonic Orchestra. The conductor was Mr. Umeda.

It had been an intense one month preparing for this day. My task was to uncover the ideal sounds which had only existed in the composer's head and then bring them out to the real world. The opportunity to do something like this is rare, because only the first performer has the privilege to present his/her interpretation without any preconception. Thus, it imparts grave responsibility upon the first performer.

At the first rehearsal on 25th, perhaps it was the extreme excitement which made my mind blank for a short instance when the orchestra began playing the introductory part.

Before the rehearsal I had run through in my mind this entire piece many times over. Yet when the time came for the solo to enter, I stood motionless and had to ask the conductor to stop. I mumbled for several seconds, flipping over the scores, "This is different from what I had expected." After thirty or forty seconds, my mind reset itself. Based on my past experience, I knew that whenever such incidents occurred, I could raise my concentration level up a notch. So I told myself, "OK, the initiation ceremony for this new piece is over. Let's march on."

With every subsequent rehearsal with the orchestra, I came to distinguish better the roles of different instruments, the entrances of important thematic phrases, and the chain of relationships that made the entire piece a coherent work of art. My interpretation of this work grew clearer.

There was long and loud applause after the concert, listeners came to offer their comments. I was delighted to hear some say, "I could sense how you resonated with this work and I was also moved." When the composer Niimi came and said, "Even though it was my piece, I was very moved by your playing," I realized that my task had been successfully completed. A sense of relief, fulfillment, and happiness spread throughout my body.

The attached picture was taken at a party following the concert. The reason why Mr. Niimi's picture is blurred below is because he was sipping excellent local sake (Japanese rice wine).

During the several rehearsal days we spent together, Mr. Niimi expressed a number of thought-provoking views on music. Among them one statement sticks out in my mind above all others: "I do not seek another innovative sound in music. I only search for the original and truthful sound for myself."

When Mr. Niimi is searching and aspiring for the origin of all sounds, his methods of creation are certainly different from those employed by Bach, but on the consciousness level these two composers probably share something in common.

Lastly, let me report to you on our performance of the second movement which contains the ninth-interval section. Strong dissonant vibration, which caused me nausea in my practice room, disappeared in the large concert hall and blended beautifully with the sounds of orchestra. This mysterious atmosphere of the concerto mesmerized the audience.

I sincerely hope in the coming days many orchestras around the world will play this magical classic which can engage the listener to share in the experience of a universal theme and awareness.

It had been an intense one month preparing for this day. My task was to uncover the ideal sounds which had only existed in the composer's head and then bring them out to the real world. The opportunity to do something like this is rare, because only the first performer has the privilege to present his/her interpretation without any preconception. Thus, it imparts grave responsibility upon the first performer.

At the first rehearsal on 25th, perhaps it was the extreme excitement which made my mind blank for a short instance when the orchestra began playing the introductory part.

Before the rehearsal I had run through in my mind this entire piece many times over. Yet when the time came for the solo to enter, I stood motionless and had to ask the conductor to stop. I mumbled for several seconds, flipping over the scores, "This is different from what I had expected." After thirty or forty seconds, my mind reset itself. Based on my past experience, I knew that whenever such incidents occurred, I could raise my concentration level up a notch. So I told myself, "OK, the initiation ceremony for this new piece is over. Let's march on."

With every subsequent rehearsal with the orchestra, I came to distinguish better the roles of different instruments, the entrances of important thematic phrases, and the chain of relationships that made the entire piece a coherent work of art. My interpretation of this work grew clearer.

There was long and loud applause after the concert, listeners came to offer their comments. I was delighted to hear some say, "I could sense how you resonated with this work and I was also moved." When the composer Niimi came and said, "Even though it was my piece, I was very moved by your playing," I realized that my task had been successfully completed. A sense of relief, fulfillment, and happiness spread throughout my body.

The attached picture was taken at a party following the concert. The reason why Mr. Niimi's picture is blurred below is because he was sipping excellent local sake (Japanese rice wine).

During the several rehearsal days we spent together, Mr. Niimi expressed a number of thought-provoking views on music. Among them one statement sticks out in my mind above all others: "I do not seek another innovative sound in music. I only search for the original and truthful sound for myself."

When Mr. Niimi is searching and aspiring for the origin of all sounds, his methods of creation are certainly different from those employed by Bach, but on the consciousness level these two composers probably share something in common.

Lastly, let me report to you on our performance of the second movement which contains the ninth-interval section. Strong dissonant vibration, which caused me nausea in my practice room, disappeared in the large concert hall and blended beautifully with the sounds of orchestra. This mysterious atmosphere of the concerto mesmerized the audience.

I sincerely hope in the coming days many orchestras around the world will play this magical classic which can engage the listener to share in the experience of a universal theme and awareness.

Next week I will play the world premiere of Mr. Tokuhide Niimi's Violin Concerto no. 2.

Today I had the first meeting on this concerto with Mr. Niimi and played for him, and asked for his opinion.

With a brand new piece, at first I always start by trying to find the effective fingerings and bowings for my part. Then, I mark the orchestral score with color pencils areas where I need to pay special attention. Slowly the bland black and white notes take on a life of their own, and as I keep practicing, more vivid emotions arise inside me. This process may be similar for an actor who is handed a script to prepare for a new role. I say so because musicians and actors have to resonate ultimately with the roles and the contents of the art work.

The second movement opens with dissonance intervals of a ninth. My solo part stays at this interval for a substantial amount of time and reaches a very high pitch, then descends rapidly to the lowest G! I find this passage quite demanding.

This ninth creates strong and peculiar vibration throughout my upper body and I feel nausea while I play. It took quite a number of hours of practice to get used to this. But don't be too concerned, as the listeners will feel no pain. Only the soloist feels the rushing energy! I was surprised to learn that sound produces so much vibration and impact on my body!

After the meeting, Mr. Niimi invited me to a concert in Tokyo, which featured a number of world premieres for percussion instruments. Besides Mr. Niimi, the composers included Messrs. S. Ikebe, A. Nishimura, H. Ito and Ms N. Kaneko. And Mr. S. Satoh was in the audience. Mr. Nishimura and Mr. Satoh visited and gave lectures about their compositions at my university several times.

Among the performances that night I became especially interested in two new pieces which Mr. Niimi and Mr. Nishimura had composed for marimba, since I had already scheduled a concert in 2010 with a promising young marimba player. This evening, the marimba player, Ms. S. Yoshihara, made wonderful execution with warm, articulated sounds with many layers of colors. I began to explore different possibilities of how violin and marimba could play together.

Today I had the first meeting on this concerto with Mr. Niimi and played for him, and asked for his opinion.

With a brand new piece, at first I always start by trying to find the effective fingerings and bowings for my part. Then, I mark the orchestral score with color pencils areas where I need to pay special attention. Slowly the bland black and white notes take on a life of their own, and as I keep practicing, more vivid emotions arise inside me. This process may be similar for an actor who is handed a script to prepare for a new role. I say so because musicians and actors have to resonate ultimately with the roles and the contents of the art work.

The second movement opens with dissonance intervals of a ninth. My solo part stays at this interval for a substantial amount of time and reaches a very high pitch, then descends rapidly to the lowest G! I find this passage quite demanding.

This ninth creates strong and peculiar vibration throughout my upper body and I feel nausea while I play. It took quite a number of hours of practice to get used to this. But don't be too concerned, as the listeners will feel no pain. Only the soloist feels the rushing energy! I was surprised to learn that sound produces so much vibration and impact on my body!

After the meeting, Mr. Niimi invited me to a concert in Tokyo, which featured a number of world premieres for percussion instruments. Besides Mr. Niimi, the composers included Messrs. S. Ikebe, A. Nishimura, H. Ito and Ms N. Kaneko. And Mr. S. Satoh was in the audience. Mr. Nishimura and Mr. Satoh visited and gave lectures about their compositions at my university several times.

Among the performances that night I became especially interested in two new pieces which Mr. Niimi and Mr. Nishimura had composed for marimba, since I had already scheduled a concert in 2010 with a promising young marimba player. This evening, the marimba player, Ms. S. Yoshihara, made wonderful execution with warm, articulated sounds with many layers of colors. I began to explore different possibilities of how violin and marimba could play together.

Recently I went to see a Japanese film, The Sun That Never Sets, which starred Ken Watanabe as the main character. Earlier this year, I had happened to watch a TV drama in which he had given a tour de force performance as a detective. Usually I go to cinema only after hearing good reviews, but not this time. "If Watanabe (an Oscar nominee in 2008) is in the film, got to be an interesting film," I thought.

Unfortunately my reaction to The Sun That Never Sets was same as I had after watching another big budget film, The Red Cliff . Both films have many famous actors in them, but I couldn't find a clear message from the two film directors. While I have not read the original novel, The Sun That Never Sets, by Yamazaki (a well-known contemporary woman novelist in Japan), I suspect I would have been moved more by reading the novel than by watching this film.

When an artist/director adapts a work of art originally created in one medium for another medium, she has to decide which parts of the original to emphasize and keep and which to eliminate so as to convey a clear message to the audience.

The film director of The Sun That Never Sets could have focused on the internal struggle of the main character (played by K. Watanabe) and spent much less time trying to recreate every event in the novel. This way, the director could have succeeded in convincing the audience why at the end, when the protagonist sees the endless sky and expansive savanna of Kenya, he finds peace and reconciliation with the world.

While watching this film, I recalled a comment made by Mr. Soumei Sato, one of the leading composers in Japan. Earlier in June of this year, I had invited Mr. Sato to come to our university, Akita International University, and lecture for three days.

In his lecture, Mr. Sato chose two films: Ron Ricke's Baraka (1992) and Masaki Kobayashi' s Kwaidan (1965). The subtitle to the film Baraka is "A World Beyond Words". Many stunning sceneries of the earth follow one after another on the screen. This film has no words, only music, including a piece composed by Mr. Sato years before the film.

When the showing of the film was over and the large lecture room's lights came on, a big sigh and rumble broke out among the students. Mr. Sato's first comment to the students was shocking to many students, "The film director relied too much on music. I think we don't need music for this film." To these words I was alone applauding loudly.

He added, "The film director should be more confident about the messages which the photographs can provide. One shouldn't distort the message by adding music to the pictures."

He is so right. Musicians know, with appropriate arrangement of notes and use of harmony, music has that special power to elicit a particular feeling or emotion in humans. When one adds an inappropriate music to the video, the intent of the video can get blurred dramatically. For example, in Baraka there is a cremation ceremony scene along the Ganges River. I recall the accompanying music was way too grandiose, and this clear mismatch made me uncomfortable. I felt strongly throughout the film that the sounds were actually hindering the natural yearning of the viewer to tune in to the message the photographs were trying to transmit. Thus, a film director must take extreme caution to make sure that music augments the message that his video is conveying. A good combination of image and sound will allow each viewer to interpret the message by himself without feeling being coerced to feel a particular emotion.

In the film, The Sun Never Sets, I was concerned about how music was used. Even before a particular set of video images came onto the screen, music was used to elicit a certain type of predetermined emotion (that a viewer was expected to feel several seconds later.) Under such circumstances, there was no way a viewer could have a deeply moving experience. Unfortunately, this unwelcome pattern persists in many mediocre Japanese samurai movies or low budget TV dramas.

We musicians know the magical power that sounds have. Perhaps that's why we don't want to listen to music just for fun. In this present world, music is used and consumed recklessly and without much thought. The net result is that humans have become numb toward the real power of sounds.

For his lecture, Mr. Sato chose another movie called Kwaidan, in which Toru Takemitsu (probably the best-known twentieth-century Japanese composer in the world) composed the background music specifically for this film. (Kwaidan is a collection of short horror or mysterious tales.)

According to Mr. Sato, an unparalleled team work between the film director and the composer created this lasting masterpiece. He went on to describe in one tale, Earless Monk Hoichi, the singing by the late Kinshi Tsuruta and her powerful playing of the Japanese lute (biwa) magnifies the feeling evoked by the visual shots of the tragic battle between the two clans in the 12 century.

Kinshi Tsuruta is credited for re-introducing the beauty and power of Japanese lute and accompanying singing to the world. If you have not seen the film, I hope you will take the trouble to rent a DVD, learn about this magnificent artist, and appreciate the genius of a woman who unfortunately died so young.

Unfortunately my reaction to The Sun That Never Sets was same as I had after watching another big budget film, The Red Cliff . Both films have many famous actors in them, but I couldn't find a clear message from the two film directors. While I have not read the original novel, The Sun That Never Sets, by Yamazaki (a well-known contemporary woman novelist in Japan), I suspect I would have been moved more by reading the novel than by watching this film.

When an artist/director adapts a work of art originally created in one medium for another medium, she has to decide which parts of the original to emphasize and keep and which to eliminate so as to convey a clear message to the audience.

The film director of The Sun That Never Sets could have focused on the internal struggle of the main character (played by K. Watanabe) and spent much less time trying to recreate every event in the novel. This way, the director could have succeeded in convincing the audience why at the end, when the protagonist sees the endless sky and expansive savanna of Kenya, he finds peace and reconciliation with the world.

While watching this film, I recalled a comment made by Mr. Soumei Sato, one of the leading composers in Japan. Earlier in June of this year, I had invited Mr. Sato to come to our university, Akita International University, and lecture for three days.

In his lecture, Mr. Sato chose two films: Ron Ricke's Baraka (1992) and Masaki Kobayashi' s Kwaidan (1965). The subtitle to the film Baraka is "A World Beyond Words". Many stunning sceneries of the earth follow one after another on the screen. This film has no words, only music, including a piece composed by Mr. Sato years before the film.

When the showing of the film was over and the large lecture room's lights came on, a big sigh and rumble broke out among the students. Mr. Sato's first comment to the students was shocking to many students, "The film director relied too much on music. I think we don't need music for this film." To these words I was alone applauding loudly.

He added, "The film director should be more confident about the messages which the photographs can provide. One shouldn't distort the message by adding music to the pictures."

He is so right. Musicians know, with appropriate arrangement of notes and use of harmony, music has that special power to elicit a particular feeling or emotion in humans. When one adds an inappropriate music to the video, the intent of the video can get blurred dramatically. For example, in Baraka there is a cremation ceremony scene along the Ganges River. I recall the accompanying music was way too grandiose, and this clear mismatch made me uncomfortable. I felt strongly throughout the film that the sounds were actually hindering the natural yearning of the viewer to tune in to the message the photographs were trying to transmit. Thus, a film director must take extreme caution to make sure that music augments the message that his video is conveying. A good combination of image and sound will allow each viewer to interpret the message by himself without feeling being coerced to feel a particular emotion.

In the film, The Sun Never Sets, I was concerned about how music was used. Even before a particular set of video images came onto the screen, music was used to elicit a certain type of predetermined emotion (that a viewer was expected to feel several seconds later.) Under such circumstances, there was no way a viewer could have a deeply moving experience. Unfortunately, this unwelcome pattern persists in many mediocre Japanese samurai movies or low budget TV dramas.

We musicians know the magical power that sounds have. Perhaps that's why we don't want to listen to music just for fun. In this present world, music is used and consumed recklessly and without much thought. The net result is that humans have become numb toward the real power of sounds.

For his lecture, Mr. Sato chose another movie called Kwaidan, in which Toru Takemitsu (probably the best-known twentieth-century Japanese composer in the world) composed the background music specifically for this film. (Kwaidan is a collection of short horror or mysterious tales.)

According to Mr. Sato, an unparalleled team work between the film director and the composer created this lasting masterpiece. He went on to describe in one tale, Earless Monk Hoichi, the singing by the late Kinshi Tsuruta and her powerful playing of the Japanese lute (biwa) magnifies the feeling evoked by the visual shots of the tragic battle between the two clans in the 12 century.

Kinshi Tsuruta is credited for re-introducing the beauty and power of Japanese lute and accompanying singing to the world. If you have not seen the film, I hope you will take the trouble to rent a DVD, learn about this magnificent artist, and appreciate the genius of a woman who unfortunately died so young.

Yesterday I was invited to a party to celebrate fifty years of teaching by a Japanese violin teacher、K. Satoh. His face looked radiant with happiness and fulfillment, surrounded by so many young and older pupils. .

One needs many favorable factors to stay on his occupation for more than fifty years. When the values of the world change, people's tastes end up in different directions and the idea of keeping up both motivation and good health--balancing all of these things for half a century--makes me dizzy. In any field, I suspect, if a person keeps at one activity for a very long time, he has a chance to arrive at the essence of the truth. But there is no guarantee that everyone who tries will reach this ultimate goal.

Nathan Milstein, one of the greatest violinists of the twentieth century, who lived to 87 and with whom I had some lessons, said his one gift from God was that he could continue to grow even in his last years. My teacher at the Juilliard School, Joseph Fuchs, kept practicing every morning for two hours even when he was in his 90's. Some days he would phone me and brag about a new insight or fingerings he had just discovered.

In "The Art of Violin", I. Perlman mentions for anyone to keep playing violin beyond the age of forty is a miracle. In this profession, he adds, it is far more likely that events in life would push the artists to quit. I am grateful to have been able to perform for so many years and am still determined to develop my distinct style.

A week ago, a Mongolian sumo grand champion, Asashoriu, won a major tournament in Japan. While I am not a devoted fan of sumo wrestling, when I have time I watch the bouts from time to time. For an athlete whose asset is primarily his physical body, the effective years on the competitive stage are limited. Nonetheless, I marvel at this Mongolian wrestler who continues to wrestle despite injuries and many negative comments thrown at him by the media. The media has hounded him for years for not practicing enough, and yet he has won many championships.

I, as a musician, is very much drawn to a super athlete like him who can instantly recognize and correct his mistakes and prepare for the next bout. Given that he has won 24 championships without serious practice and serious rivals, at some point he must have stopped developing.

In order to reach the apex of a profession, one needs a set of circumstances. The professional baseball player Ichiro of Seattle Mariners has both talent and a hunger for improvement and self discipline. His uncompromising dedication to analyzing himself and finding answers is what Milstein calls, "Gift from God". A man who is born with talent as well as this gift from God, we call him a genius.

One needs many favorable factors to stay on his occupation for more than fifty years. When the values of the world change, people's tastes end up in different directions and the idea of keeping up both motivation and good health--balancing all of these things for half a century--makes me dizzy. In any field, I suspect, if a person keeps at one activity for a very long time, he has a chance to arrive at the essence of the truth. But there is no guarantee that everyone who tries will reach this ultimate goal.

Nathan Milstein, one of the greatest violinists of the twentieth century, who lived to 87 and with whom I had some lessons, said his one gift from God was that he could continue to grow even in his last years. My teacher at the Juilliard School, Joseph Fuchs, kept practicing every morning for two hours even when he was in his 90's. Some days he would phone me and brag about a new insight or fingerings he had just discovered.

In "The Art of Violin", I. Perlman mentions for anyone to keep playing violin beyond the age of forty is a miracle. In this profession, he adds, it is far more likely that events in life would push the artists to quit. I am grateful to have been able to perform for so many years and am still determined to develop my distinct style.

A week ago, a Mongolian sumo grand champion, Asashoriu, won a major tournament in Japan. While I am not a devoted fan of sumo wrestling, when I have time I watch the bouts from time to time. For an athlete whose asset is primarily his physical body, the effective years on the competitive stage are limited. Nonetheless, I marvel at this Mongolian wrestler who continues to wrestle despite injuries and many negative comments thrown at him by the media. The media has hounded him for years for not practicing enough, and yet he has won many championships.

I, as a musician, is very much drawn to a super athlete like him who can instantly recognize and correct his mistakes and prepare for the next bout. Given that he has won 24 championships without serious practice and serious rivals, at some point he must have stopped developing.

In order to reach the apex of a profession, one needs a set of circumstances. The professional baseball player Ichiro of Seattle Mariners has both talent and a hunger for improvement and self discipline. His uncompromising dedication to analyzing himself and finding answers is what Milstein calls, "Gift from God". A man who is born with talent as well as this gift from God, we call him a genius.

I am presently rehearsing for a concert in Chiba City (an hour's drive from Tokyo) in two days. This concert is sponsored by Komai Tekko Inc., a leading company in Japan which specializes in design and installation of long bridges, elevated highways, and wind power systems.

As the last piece of this concert, I chose a sonata by Ysaÿe for two violins and invited a long time friend, Tracy, to fly in from Taipei. Subsequently we agreed to play the same piece again in a different concert in Taipei later in the month.

Right now I have two concerns : first, the latest weather forecast which is predicting a typhoon to arrive on the date of the concert; the second, while we are performing, there are no convenient spots to turn the music scores throughout each movement. Of course, this would not be a problem if we memorize the entire twenty five minutes piece.

In the case of Prokofiev's sonata for two violins, we face a similar difficulty on deciding when to turn pages in a very short time. In most other pieces, however, there are usually suitable places to do so.

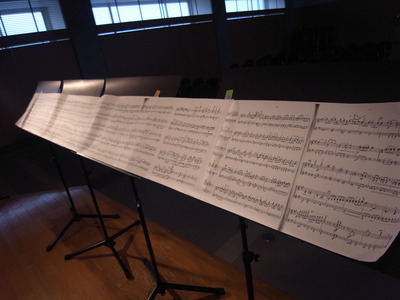

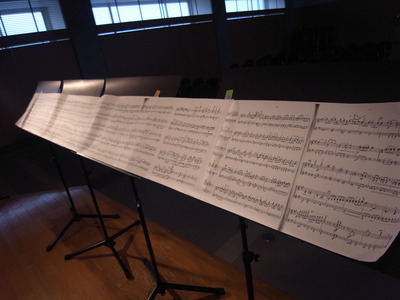

After struggling for a while, we experimented spreading the sheets of music over four music stands and tried moving to the right as each movement progressed. This method was troublesome because the first movement had sixteen pages; the second, nine pages; and the third, twelve pages. Therefore, we first laid the pages for the third movement on the music stands, then on top of them, we placed the pages for the second movement, and finally the pages for the first movement. When we finished playing one movement, we had to remove the pages of what we had just played. Unfortunately this removing process took too much time and affected the flow of music.

What to do?

A manager at the Komai Tekko Inc. came up with an innovative proposal. In his line of business, sometimes his designers have to create an unusually long, continuous document. This document is then rolled up into a scroll and is carried around from place to place. Thanks to this brilliant idea, we had a scroll of music made for each movement in no time. This way we were able to keep the break between movements to a minimum.

Attached below is a photograph of the super-long music score. Later I will carefully carry these scrolled scores to Taipei and use them again at a concert.

As the last piece of this concert, I chose a sonata by Ysaÿe for two violins and invited a long time friend, Tracy, to fly in from Taipei. Subsequently we agreed to play the same piece again in a different concert in Taipei later in the month.

Right now I have two concerns : first, the latest weather forecast which is predicting a typhoon to arrive on the date of the concert; the second, while we are performing, there are no convenient spots to turn the music scores throughout each movement. Of course, this would not be a problem if we memorize the entire twenty five minutes piece.

In the case of Prokofiev's sonata for two violins, we face a similar difficulty on deciding when to turn pages in a very short time. In most other pieces, however, there are usually suitable places to do so.

After struggling for a while, we experimented spreading the sheets of music over four music stands and tried moving to the right as each movement progressed. This method was troublesome because the first movement had sixteen pages; the second, nine pages; and the third, twelve pages. Therefore, we first laid the pages for the third movement on the music stands, then on top of them, we placed the pages for the second movement, and finally the pages for the first movement. When we finished playing one movement, we had to remove the pages of what we had just played. Unfortunately this removing process took too much time and affected the flow of music.

What to do?

A manager at the Komai Tekko Inc. came up with an innovative proposal. In his line of business, sometimes his designers have to create an unusually long, continuous document. This document is then rolled up into a scroll and is carried around from place to place. Thanks to this brilliant idea, we had a scroll of music made for each movement in no time. This way we were able to keep the break between movements to a minimum.

Attached below is a photograph of the super-long music score. Later I will carefully carry these scrolled scores to Taipei and use them again at a concert.

Recent Comments